This is an example of the material I'm publishing, sometimes daily, on Substack (free). To subscribe and have columns delivered to your email, go to : https://betsyrobinson.substack.com/

Why would I, a liberal progressive who watched every second of the January 6, 2021, hearings about the attack on the Capitol, want to watch and review a documentary film about Adam Kinzinger, the former Republican Congressman from Illinois who bucked his party and was a member of the Select Committee to investigate what happened?

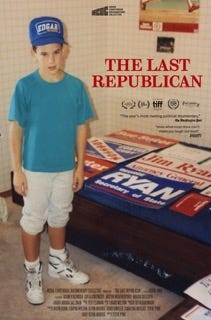

One might ask a similar question about filmmaker of The Last Republican, Steve Pink, an avowed "leftie" who Kinzinger knew from his film Hot Tub Time Machine (which I have not seen)—why would he want to devote a year of his life to making this movie?

The answer to both questions is LOVE—for love of honorable people. Kinzinger and Pink both reveal themselves to be that—Pink most often from the sidelines asking Kinzinger questions—and their affection for one another, within a mutual language of humor, is palpable.

Pink's 85-minute documentary, The Last Republican, pulses with truth and mutual respect, and therefore more powerfully conveys the history of what happened after the January 6th attempted coup as well as the reality that when two people with radically opposed beliefs come together with a common ground of truth, there can be love.

The Last Republican, which I saw at NYC's Film Forum in January 2025, opens with Kinzinger needling Pink about their opposing beliefs, but it quickly gets serious. We follow the history of the violent attack on the Capitol to attempt to overthrow the certification of the election, to what has become known as The Big Lie—Trump's continued claim that the election was rigged—to a recap of testimony. Even though I was glued to the entire run of the hearings, I was moved anew at the Capitol Police officers' recounts of "tragedy and sadness and defeat," which so gutted Kinzinger's pregnant wife Sofia, that she texted him from home: "Remind them that they won." … Which Kinzinger did, with gratitude and tears that ripped my heart open and, I wager, touched everybody in the Film Forum audience.

And the fact that the documentary cuts from this to Newsmax and Fox News's Tucker Carlson mocking Kinzinger's vulnerability evoked an audible gasp. It was not merely jarring; it was like seeing an ignoramus making fun of the nakedness of Michelangelo's David.* I felt so sorry for Carlson's inability to see what we were seeing: a completely open-hearted man whose every action is to help.

The film follows Kinzinger's decision not to run again after his district is redrawn to make a win impossible; we are generously invited into his life, his parents' life, and the arrival of his new son. We sit with him as the Republican Party votes to censure him, kicking him out of the party; as he recounts losing all his friends; and as the threats explode, requiring 24-hour security. And he becomes more and more lovable—not just to us but to the people around him: his home security team becomes invested in his baby's sleep training. His parents, who have a similar humor to Adam's, disparage family who insist on voicing their dislike to Adam's mom. But what never changes is Kinzinger's calm knowing that he did the right thing because there was a line he could not cross.

We learn the history of this from his childhood, to risking his life in Milwaukee for a stranger who was being attacked and bleeding out in a parking lot. At the time, Kinzinger was fresh from Air Force training (he joined following 9/11). Once we experience this incident in Kinzinger's raw retelling, we understand this man deeply. And love him more.

"Any courage I show comes from I just want to be able to look myself in the mirror," he answered when asked about the anomaly of his actions after January 6th. "I really don't think what I did is so courageous. It's just that I'm surrounded by cowards."

Steve Pink reminds him about the Milwaukee attack: "That was courageous."

Kinzinger first says it was stupid because you should never get in a fight with a person with a knife. But after reflection, "When you make the decision to give your life up for a stranger …[he pauses, tearing up]…I mean how can't that change you?"

When Pink asks about the next part of his life, Kinzinger says he will be in a fight against cynicism. "I don't want in the second half of my life to not be willing to put my life on the line for people."

Pink: "Even MAGA people?"

Kinzinger: "Yeah, even MAGA people. Maybe especially them because they need some inspiration that they're not getting. They're being lied to and abused."

As the film ends, Pink and Kinzinger embrace like bros. And as they walk off screen:

Pink: "If this documentary helps you win the presidency and you enact horrible conservative policies, I swear to fucking god—

Kinzinger: "Oh, I'll call my first horrible policy the Steve Pink Conservative Future Bill."

What Is an Honorable Person?

In a review/essay of First Principles: What America's Founders Learned from the Greeks and Romans and How that Shaped the Country, by historian Thomas E. Ricks, writer Richard Werber writes:

Merriam-Webster defines honorable as "deserving of respect or high regard" or "of great renown." "Honorable" is something earned from past behavior. But for the Founders, it was specific to judging behavior in the moment. And its meaning was clear. It was more than being honest. To be honorable, to make honorable decisions, was to consider and act as much, or more, for the welfare and happiness of others as for oneself.

The Last Republican is a stirring and affirmative (about our ability to get along with our disagreements) portrait of two honorable men: Adam Kinzinger and filmmaker Steve Pink.

_____________________________

* Interestingly, Michelangelo's David represented, not only great male beauty, but the defense of civil liberties embodied in the 1494 constitution of the Republic of Florence, a city-state under siege.

_____________________________

To join Adam Kinzinger's nonpartisan group in actions to save our democracy, go to Country First, with 300,000 active members, and counting.

Per Country First's action emails:

Our Days of Action have empowered nearly 9,000 volunteers, because they are a time designed to equip and empower you for action. Days of Action are meant to help you answer the question, "how do I make a difference?" And it's going to show you that taking effective action is easier than you might think.

The Last Republican is not currently streaming, but you can sign up to receive a notice when it is available: https://vurchel.com/v/31034/the-last-republican-steve-pink.

In the meantime, enjoy the trailer: