"At no other time in history," said Amor Towles, author of A Gentleman in Moscow (which I've swooned over) and Rules of Civility (which I will read very soon), "at no other time have fiction writers been held to a higher standard of truth than people who run for political office."

Big laugh! We were a packed audience at a talk Towles was giving at the National Arts Club located on Gramercy Park South, one of the most elegant addresses in New York City and a fitting venue for a writer as elegant as Towles in his perfectly fitted brown pin-stripe suit. He continued: "Someone running for the highest office in the land can say anything, the most outrageous lies, and be excused, yet if I get an address wrong in a novel, I receive a million irate emails."

Another laugh.

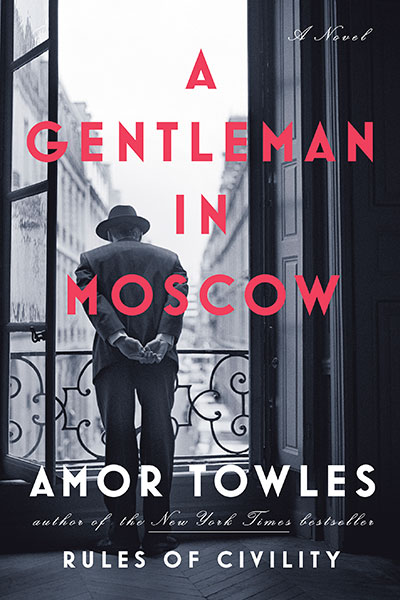

I'd been blown away by the glorious and romantic storytelling of A Gentleman in Moscow, about aristocrat Count Alexander Rostov who is sentenced by the revolutionary Bolshevik government to house arrest in the posh Metropol Hotel in Moscow (think Eloise in the Plaza if she were a 30-year-old gentleman living in 1922 Moscow, as told by a fine literary writer who spews poetry from his taste buds and history from his pores), and I'd just assumed it was deeply researched and historically accurate. And I could not wait to hear Amor Towles read.

Surprise! He didn't. Wouldn't. And that's fine. What he did do was masterfully share a complete history of Moscow and the Metropol during the Russian Revolution (even managing to illuminate the Russian psyche of today: Putin is popular because Russians deeply believe they deserve to be a world power and they will give up rights because they are confident that Putin can make that happen), and answer questions about the book.

Of all of his answers, I found most fascinating his explanation about the importance of historical research and accuracy. He does no background research before writing, but instead works from what he's already involved in and excited about (a lot; he is a true Renaissance man), and only then — after a first draft — he will do some research because he doesn't want to impede his imagination with historical facts when the solidly outlined idea is being birthed. He feels that that kind of research can bog you and the writing down if you are so married to facts from the beginning. (Bravo! I have an aversion to the habitual fact-dumping in the genre of historical fiction; it's fine to research; not fine to inhibit artistic flow by compulsively dumping it into almost every sentence and description.)

In Amor Towles I think I witnessed the embodiment of the freedom I felt in his writing: true flow, derived from being so prepared with the fruits of disciplined curiosity that he's completely spontaneous and comfortable in his own skin. Kind of like his character Count Rostov in A Gentleman in Moscow.